אוצרת: הדס גלזר

צילום: הדס חי

בתערוכת היחיד פרזיטית פורשת האמנית רחלי טאובר התבוננות רחבה במושג "ערך" על היבטיו השונים, כפי שאלו נכרכים באיכות חומרית, בעבודה אנושית ובקטגוריות זהות: כיצד קובעת החברה את ערכם של אנשים, של חפצים ושל עבודה, וכיצד משפיעות הגדרות אלה על מעמדו של הפרט באותה חברה? בעבודות הממזגות יחד מלאכה עם אמנות וחומרים "גבוהים" עם חומרים "נמוכים", האמנית מערערת על האופן שבו נמדד ערכו של האדם בתוך המבנה החברתי.

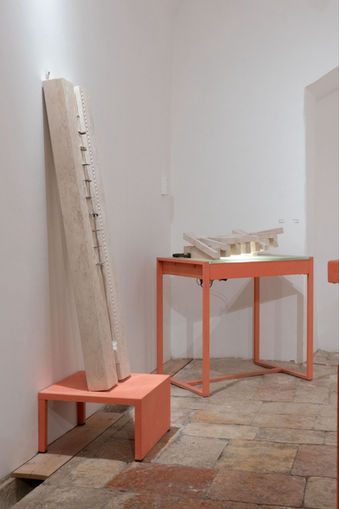

הפסלים עשויים מאבן שיש, כלי עבודה משומשים, חלקי מתכת וחוטים. טאובר משתמשת בטכניקות פיסול מסורתיות שכוללות סיתות, קידוח ותכנון הנדסי, כדי לרכך את אופיו הקשיח של השיש ולהטעינו במשמעויות חדשות. שילוב כלי העבודה השחוקים – שחלקם שימשו בתהליך היצירה – בפסלים עצמם, מדגיש את המתח שבין חומריות לאידיאולוגיה, בין יציבות לשבריריות, בין מלאכות נשיות לאלו שנחשבות גבריות ובין אמנות לעמל כפיים. כנגד ההוד של אבן השיש הלבנה, הכלים החלודים חושפים את מה שמערכות הייצור מבקשות להסתיר: המאמץ, היזע והשחיקה המשוקעים בייצור וביצירה.

שם התערוכה, פרזיטית, מתכתב עם סטריאוטיפים מגדריים ותרבותיים. טאובר מבקשת להתמודד עם הדימוי של "אישה פרזיטית" – מונח טעון הנתפס כתלותי או נצלני – והופכת אותו לאמירה מורכבת על זהות, ערך ושיוך חברתי. בעבודותיה ניכרות השפעות מגוונות שכוללות את תולדות האמנות הישראלית ופיסול מודרניסטי נוסח יחיאל שמי ועזרא אוריון, רדי־מייד דאדאיסטי, סמלים יהודיים, מוטיבים מעולם התפירה והטקסטיל וציירי מופת, כגון ורמיר. החיבור בין המסורות הללו מתחדד מנקודת מבטה הייחודית, השואבת מן העולם החרדי שבו גדלה – עולם הנתפס לעיתים כמתנגש עם האמנות העכשווית, בעלת הנטיות החילוניות והמערביות. מעצם ההצלבה של נושאים אלו צפות ועולות שאלות על מעמד עבודת קודש ועבודת אמנות, על מעמד האמנים ומעמד החרדים בחברה, על שווי פרי עבודתם ועל חשיבותה – או שמא חוסר חשיבותה – של יצירת האמנות במציאות החברתית־כלכלית של ימינו.

על ידי שילוב חומרים וטכניקות מגוונות, טאובר מציעה פרשנות חדשה על זהות, עבודה וערך חברתי. בעבודתה, האבן הכבדה מתרוממת בעזרת תמיכות קלות ונסתרות, בעוד שכלי העבודה השחוקים מספרים סיפור של עמל שקוף, כאשר החומר הופך מנקודת מוצא פיזית לדיון עמוק בזהות ובמעמד חברתי. בכך, טאובר מציבה תזכורת: הערך אינו תלוי בכימות או בתוצרים בלבד, כי אם טמון במשמעות הפנימית של החומר ושל העשייה, במאמץ הסמוי וביופי החד־פעמי הגלום בתהליך היצירה.

Curator: Hadas Glazer

Photos: Hadas Hay

In her solo exhibition Parasite, Rachel Tauber unfolds a broad observation of

the concept of “value” in its various aspects, as they are bound up with material quality, human labor, and identity categories: How does society determine the value of people, objects, and labor, and how do these definitions affect the status of the individual in that society? In works that merge craft with art and “high” with “low” materials, the artist challenges the

way in which the value of a person is measured within the societal structure.

The sculptures are made of marble, well-used tools, metal scraps, and

threads. Combining traditional sculpture techniques like chiseling and drilling with careful engineering design, Tauber strives to soften the hard nature of the marble and imbue it with new meanings. The incorporation of worn tools – some of which were used in the creation process – into the sculptures themselves highlights the tension between materiality and ideology, between stability and fragility, between feminine crafts and those considered masculine, and between art and manual labor. Set against the majesty of the white marble, the rusty tools reveal what the production systems seek to hide: the effort, the sweat, and the wear and tear entailed in the production process.

The exhibition’s title, Parasite, resonates with gender and cultural

stereotypes. Tauber seeks to confront the image of the “parasitic woman” – a thorny term usually associated with dependence or exploitation – and transforms it into a complex statement about identity, value, and social belonging. Her works show diverse influences, including the history of Israeli art and modernist sculpture, like the works of Yechiel Shemi and Ezra Orion, the Dadaist ready-mades, Jewish symbolism, motifs from the world of sewing and textiles, and the works of the Old Masters like Vermeer. The connection between these traditions is underscored through her unique lens, which draws from the Haredi world in which she grew up – a world that is sometimes perceived as conflicting with contemporary art, which has secular and Western tendencies. The intersection of these themes summons questions about the status of sacred work and artistic work, the status of artists and of Haredim in society, the value of the fruit of their labor, and the importance – or lack thereof – of creating art in today’s socioeconomic reality.

By combining diverse materials and techniques, Tauber offers a new interpretation of identity, work, and social value. In her work, the heavy stone

is lifted by light, hidden supports, while the worn tools tell a story of transparent labor, as the material transforms from a physical starting point into a profound discussion of identity and social status. With that, Tauber offers us a reminder: Value does not depend on quantification or products alone, but rather lies in the inner meaning of the material and the making, in the hidden effort and the unique beauty inherent in the creative process.

%20(6).png)